Independence Day may have come and gone, but Fourth of July weekend continues. So in honor of all things "four", I'm asking myself a grueling question. Why oh why do movie four-quels suck? Let's backtrack for a bit. Many moons ago, I made a three-part rant about film trilogies. Specifically, the studio obsession with making them. Studios seem to love the number 3. So what on God's green Earth would ever possess them to make a fourth? Most trilogy closers aren't even done right, and yet filmmakers add more on anyway.

In my past rant, I did talk about franchises going beyond trilogies. I talked of the filmmakers thinking, for whatever reason, that their series still had potential for further stories. Ultimately, that's the reasoning behind most four-quels (besides the obvious money). I'm not here to talk about exactly WHY four-quels are made, so much as HOW. And by that I mean, how does one approach a fourth chapter in a film series? To be honest, there's no right way to do a four-quel. There are plenty of wrong ways, as history's proven. Exactly why is that? What is it about trying to execute a fourth chapter that almost universally leads to suckage? If we look at the four-quels we actually have, we may find the answer.

Now when I say "four-quel", I don't necessarily mean it's the fourth film in the series chronologically. I'm talking the fourth film released, meaning reboots and prequels aren't off the table. This is important to understand, because it's key to the thinking that goes into four-quels. Even when a four-quel is a sequel to prior films, it functions similarly to a soft reboot. That is the key to most four-quels sucking. Still don't follow? Allow me to explain.

Consider the trilogy. As outlined in my three-part rant, there's something appealing about franchises that come in 3 to filmmakers. It ultimately comes down to the fact that a good trilogy functions as one long movie. The reason for this is because individual films often have a three-act structure. Act One introduces the characters and the world. Act Two puts the characters in some kind of conflict. Act Three resolves the conflict and shows the characters going through a profound change.

If one approaches a trilogy like one long movie, then each film is like one of three acts. Hence, Movie One is the intro, Movie Two the rising conflict, and Movie Three the climax/conclusion. It's appealing to studios because it allows maximum franchise potential while (if done correctly) providing emotional heft. The three act structure as outlined is like a simplified form of Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey, a theory where all myths and legends can be boiled down to a basic formula. It's reused so much because it appeals to our basic human nature, to undergo a challenge and emerge the better for it. This is why trilogies like Lord of the Rings and the original Star Wars are so powerful, because they tell a basic hero's journey over the natural course of three films.

So, by the end of part 3, we have an airtight conclusion to our conflict. Audiences feel they've gone on this great journey with these characters, and have gotten a proper goodbye. But because everyone's gone to see the finale, studios look at the money rolling in and decide a fourth film is "required". Except that in terms of story, it often isn't. This is because the story naturally came to an end in part 3. Or even worse, a standalone story was stretched into a trilogy, and by the end it's been creatively milked to near-death (cough cough *Matrix/Pirates* cough). If a trilogy is a single entity told in three parts, then if a fourth film is attempted, it's the equivalent of making a follow-up after a logical conclusion.

It's why most people feel a fourth film is when a franchise "milks it" or "jumps the shark". Or, in Indiana Jones's case, "nukes the fridge." A fourth film isn't natural, often an unnecessary add-on to an already great (or at least semi-decent) trilogy. Filmmakers are often aware of this, so they come up with multiple options. Option one: your "trilogy" is really a series of loosely connected standalone stories. As such, it's relatively easy to make a fourth film that's a direct sequel, because the series doesn't have an over-arcing narrative.

Examples include Lethal Weapon, Shrek, Jaws, the original Superman and Batman films, Rambo, Indiana Jones, and any horror franchise ever made. The problem here is that a loosely connected film series often adheres to a story formula. Indy goes after a magical artifact. John McClane fights terrorists in X location. After four films this formula gets tired, especially since each film often expands said formula.

Think of the backlash to the nuked fridge in Indy. After rolling boulders, crashing planes, and falling tanks, Spielberg tops this basic formula by having Indy survive a nuke inside a lead-lined fridge. The basic formula, in an attempt to top itself, has gotten so silly it alienates the audience. As such, no one can get into it. For a more recent example, see Transformers: Age of Extinction, although that gets into another four-quel option.

This option follows a trilogy with an over-arcing narrative, ending with part 3. So for part 4, the filmmakers try to justify its existence by engineering a brand new story arc, often to start a new (what else?) trilogy. Filmmakers love the trilogy structure so much that if more films are made, they'll often either come as a trilogy or with the intention of making one. Examples include the aforementioned Age of Extinction, The Bourne Legacy, Alien: Resurrection, Terminator: Salvation, X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Pirates 4, Star Wars Episode I, and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.

Star Wars and the Hobbit managed to spark actual trilogies, and Transformers 4 likely will as well. Pirates has yet to be seen, but could happen. Alien continued and Terminator will, but not as direct follow-ups. This is because the new arcs were too different, alienating the core audience with a cloned Ripley, future Skynet war, or a Bourne film without Bourne. So while the franchise is profitable enough to continue, the series will now go in a different direction. See how Wolverine Origins was so bad that the franchise was retooled afterwards into First Class, followed soon after by a proper solo Wolverine flick.

Star Wars and Hobbit managed to succeed due to the strength of their franchises. However, it's telling that their follow-up arcs were NOT direct continuations of the original trilogies. They were instead prequels, with arcs that lead directly into their predecessors. Star Wars is planning to buck the trend with a new trilogy coming out soon, but even that will have a new story arc and new characters to focus on. Often when a new follow-up arc is made, it will either scale back the budget to be more affordable (Pirates 4) or blow up the budget to outdo part 3 (Transformers 4). This will either give the new arc lower stakes and thus not seem as important, or make the stakes so high there's no human connection (again, Pirates vs. Transformers).

This is why most four-quels often become prequels. It allows filmmakers to work around the problem by literally going back to the beginning, or focus on new characters with new problems. But unless those characters are as compelling as the original crew, people won't care for them. See the Star Wars prequels for proof. The prequels also show that just because it's set chronologically earlier, there's still a temptation to make the stakes "bigger". As such, the lightsaber battles go from tense duels in closed quarters to wide open, acrobatic set pieces (compare the Vader duels in V and VI to the Darth Maul duel in I).

So, knowing this, some filmmakers decide that it's toxic to even attempt another film in that canon, sequel or prequel. This is where we get the reboot. Amazing Spider-Man, this year's Robocop, and the upcoming Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice are the best examples here. After a conclusive trilogy, filmmakers decided the character's next film appearance will be a reboot, because a sequel'd be too anti-climactic and a prequel unappealing. Thus while it's technically the fourth film in the franchise, it's not a true four-quel. This can either work wonders or backfire heavily. But if a franchise must continue, odds are a reboot will do better at injecting new life into it, while keeping the original trilogy standalone for those purists out there.

This however begs the question: "can an in-canon four-quel actually succeed?" It doesn't happen very often, but it can. And this is where our final four-quel options come in. Either the films are serialized enough that the formula won't tire out, or there's an over-arcing narrative that naturally extends beyond a trilogy. What do I mean by this? Think about Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol, Live Free or Die Hard, Rocky IV, 007 Thunderball, Fast & Furious, Star Trek IV, and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.

The majority of those films were part of series that didn't have over-arcing stories. Their success lay in their formula, which was so popular it kept people coming back in droves. Thus, unlike other in-canon four-quels, these films can adhere to formula without tiring out . But at this point, the series either had to refresh the formula and make it seem new again (M: I: IV, Star Trek IV), or offer entries that started an over-arcing plot (Fast and Furious). Bond is the exception, since it has the magic formula that keeps people coming back even 50 years later.

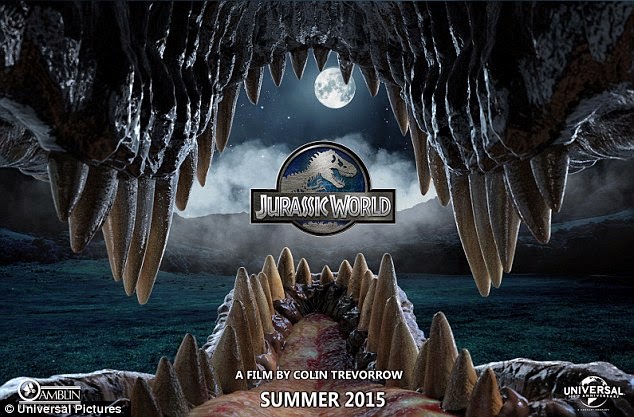

Harry Potter is the case of an over-arcing plot that goes beyond a trilogy, so part 4 is simply the next chapter rather than an unnecessary entry. It works for Harry, but only because it's based on literature. Most Hollywood sagas begin as trilogies. And for most of them, they stay trilogies until years later. Notice for Die Hard's case (and Rambo, Indy, Star Wars, and The Hobbit) the four-quel came at least a decade after the original trilogy ended, to build up demand for a follow-up entry. This is the case for next year's Jurassic World and Mad Max: Fury Road. Like the in-canon four-quels I've mentioned, they too are trying to set off a new story arc, bolstered by an entirely new cast. But because it's years later, the formula that seemed tired is now heavily missed, enough to send people flocking to theaters for part 4.

While an in-canon four-quel can work, it often doesn't. This is because, as I've stated, the four-quel either continues a now stale formula or starts an entirely different, often anti-climactic story arc. Four-quels are often made entirely for money, which is apparent in the way filmmakers construct them. Creative success comes from either embracing or refreshing the formula so it's not stale, or building a new, organic story arc that actually works. It's a lot harder than it looks, mostly because of Hollywood's trilogy obsession. And too often, successful trilogies breed terrible four-quels. There are some franchises that I'd love to see further adventures from. But until Hollywood knows how to get four-quels right, films are better off in threes.

No comments:

Post a Comment